By Daniel Magnowski

LONDON (Reuters) - Investors in commodities should look to actively managed hedge funds rather than passive indexes to get exposure to the asset class, UBS Wealth Management said on Wednesday.

Actively managed funds can time buying and selling of securities to take advantage of market opportunities, rather than sit on long positions of various commodities, as the indexes do.

Active funds can so avoid value-destroying market movements such as negative roll yield -- the cost of holding onto a security whose long-dated future price is higher than its current price.

"Given the high cyclicality and the expected changes in commodity markets in the future, investors may want to engage in a more active selection of commodities and not invest passively," UBS said in a report.

The vast majority of investment in commodities, which bankers reckon might be as much as $200 billion (106 billion pounds), is through passive indexes like the Goldman Sachs Commodities Index, but UBS said hedge funds might be a better bet.

"Investors may want to engage in more active investment strategies in this asset class. In this case, commodity hedge funds many provide a valuable alternative to a passive index-oriented investment in commodities," the Swiss bank said.

It advised that investments in natural resources would do well in years to come because greater quantities of products such as oil and industrial metals would be used in emerging markets as these countries become richer.

"The income of the average citizen in an emerging market country will likely improve relative to that of an average citizen in developed countries...future growth in demand will likely flow from emerging markets," it said.

The price of three-months copper futures on the London Metal Exchange has doubled in the past year, while crude oil is more than 10 percent more expensive now than it was 12 months ago.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Commodity Investors "Should look to Hedge Funds"

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Psst! Want a worthless guarantee?

These lousy products are still selling like hot cakes despite offering astonishingly poor value for money. Banks and building societies love them because they're a 'no-brain' sale.

Guaranteed Equity Bonds look attractive at first glance. What, invest in the stock market but get a guarantee you can't lose money and also get gains if the market rises? And all you have to do is commit the money for five years. It's a no-brainer sale for the promoter, and a no-brainer buy for the investor.

But these products prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that you should never buy an investment product unless you engage your brain and understand it. As the great US fund manager Peter Lynch once said: 'Never invest in any idea you can't illustrate with a crayon'. Even their inventors would struggle to do that with GEBs.

But I will try to explain why these products - despite being sold by Barclays, Legal & General, Bristol & West, NSI and a host of high street names - are bad value and you shouldn't buy them.

Under the bonnet

A typical GEB works like this: commit your money for five years - you can only get it back earlier if you die. At the end of the term, you get your capital back if the stock market index (the FTSE 100 Index) is at or below its original level. If the index is above that level, you get the same percentage increase in your capital. So if the index is up 10% and you invested £10,000, you get £11,000 back.

There are many variations on the theme, more on which later, but let's stick with the simple basic idea—which is pretty much what National Savings & Investments offers. The first key point is that what you get with a GEB is a return linked to the capital value of the index. But if you invested in the same shares that are in the index, or in any fund investing in those shares, you would get dividends. Right now the average yield on the FTSE 100 is 3%, and dividends are rising pretty fast - but let's be conservative and assume that they rise by an average 5% a year over a five-year term.

Then if you put £1,000 in an index-tracking fund whose price never changes over five years, the reinvestment of those dividends in more units in the fund means you will end up with an investment worth £1,176 - you will have made a return of 17.6% just from the dividends.

So to offer the true equivalent of a risk-free tracker, a GEB would have to guarantee you a minimum return of 17.6% over five years, not just a return of your capital and a return linked to the index.

Averaging can really hurt

But GEBs don't really offer the gain from the index, because almost all of them average the index over the last 12 months. They say that they do this to avoid the risk of a last-minute fall in the index damaging your investment. This isn't true. Over any period from one month to 100 years, there is a greater chance of the index rising than falling, and that means that averaging is more likely to reduce your return than to save you from a decline. But what averaging does do is to reduce the cost of buying the insurance against a decline, thus boosting the promoters' profits.

Over the past 12 months the FTSE 100 Index is up about 24%, but using the averaging methods of most of GEBs the gain over this period would have been under half of that.

So in these two respects GEBs take away significant slices of the returns earned on normal stock market investments. The question is, does the no-loss guarantee compensate you for that?

Less risky than it looks

To answer that, let's assume you have £10,000. You divide it in two. £5,000 goes into a five-year fixed rate bond paying 5%. The bond will mature with a value of £6,416. £5,000 goes into an index-tracking fund. We'll assume that because of the dividends it earns, the price of the fund can fall by 15% before you actually lose money over five years. Say it does that - so your £5,000 has fallen to £4,250. Overall, though, your £10,000 has become £10,666. In fact, the price of the tracker fund has to fall by 28% before your total capital ends up at under £10,000 at the end of five years.

How likely is that? The Barclays Equity-Gilt Study shows that of 41 five-year December-to-December periods since 1959, eight of them showed losses of over 28% - about one in five. But six of those periods were bunched together between 1968 and 1972. These figures don't correspond to those quoted by GEB providers because the Barclays figures are in real terms, i.e. adjusted for inflation, and in nominal pound-note terms loss-making periods of over 25% would have been halved.

Wait and get a recovery

And that isn't the end of the story, because periods of sharp loss in the stock market are often followed by periods of sharp gain - as in 2003, when the FTSE 100 rebounded from an exceptionally severe three-year fall of 45% with a gain of 25% and followed that with a gain of 10% in 2004. So if you hold a tracker fund you can just wait for a recovery - while with a GEB you may come out with your capital intact and miss the following gains.

All this strongly suggests that the price you pay for no-loss insurance with a GEB is far higher than it is worth paying, provided you are prepared to add a year or two to your investment period if at the end of the original five-year term the market is down.

Big bear markets like 2000-2003 are once-in-a-generation events - the last was in 1972-74. Smaller, shorter-term upsets when shares fall by 10% or 15% over a year and then recover, are something you should just take in your stride. If you want higher returns than you get from fixed-rate bonds but don't like risk, consider commercial property funds and cautious managed funds. While both can go down, they are far less volatile than shares.

Bring on the baffle-o-meter

Promoters of GEBs are pushing out into new areas. Recently we've seen GEBs linked to baskets of share indices and to commodity prices or commodity indices. Some of these offer a variant where instead of 100% capital protection, you get just 80% protection but instead of 100% of the index gain you get 200% of the index gain.

This shows what GEBs are really all about: they are a kind of betting in which the promoters are the bookmakers. Guess what: the bookies know a lot more about the form and the odds than you do - so should you be surprised that they make more money than the punters?

Some bad current offers

Bristol & West Minimum Return Bond Mini-Cash ISA

This guarantees a minimum return of 15% at maturity at the end of five years, equivalent to an annual return of 2.8%.

Barclays 6-year Minimum Return Plan Issue 16

Over six years, you get a minimum return of 21.5% which works out at 3.3% annually. If the index is up more than 43%, you get a return of half the gain in the index.

Abbey Capital Guaranteed UK Equity Bond

Over five years you get a return of 130% of the gain in the FTSE 100 index, but this is capped at a maximum return of 50%.

Most of the GEBs sold on the high street are likely to generate low returns of a few percent a year on top of deposit rates. If you want more, put some of your capital into safe fixed-rate investments. Many of these have the capacity to make handsome gains even if share prices in general show little change.

By Chris Gilchrist

Sunday, August 13, 2006

Offshore Investors beat EU Directive to avoid tax.

By Robert Budden and Josephine Cumbo - FT

Tens of thousands of investors with money tied up in offshore financial centres have been successfully exploiting loopholes in the new EU savings directive, allowing them to escape the scrutiny of tax authorities or bypass withholding taxes introduced last year under the new law.

Figures released by the Swiss Finance Ministry reveal only €100m (£69m) was raised by Switzerland – the world’s largest offshore financial centre – in the second half of 2005, the first six months of the new law’s operation.

Over the same period, Jersey raised just £9m and Guernsey just over £3m, a tiny fraction of the £70bn of assets held in these offshore financial centres.

Tax accountants said the surprisingly low figures were the latest signs that many offshore savers had channelled their money to centres such as Singapore which are not covered by the EU savings directive or had re-organised their offshore savings so they escaped the scrutiny of tax authorities.

Under the directive, which came into force in July last year, all EU member states and more than a dozen offshore financial centres from the Cayman Islands to Liechtenstein must share account holder information with relevant local tax authorities or levy withholding taxes of up to 35 per cent. The rules apply to money held in offshore savings accounts.

Tax experts said there was evidence that as well as moving money to offshore jurisdictions not covered by the directive, many savers had taken less dramatic steps to escape the directive – including moving money into deferred interest accounts where interest is paid only when the account is finally closed. Offshore insurance “wrappers” have also become more popular as these also escape the directive.

“The average amount held in these accounts before the EU savings directive was about £50,000 but now it is just shy of £100,000,” said Tim Harvey, director of HR Independent Financial Services.

Offshore insurance bonds are exempt from the directive because all the assets in the bonds are technically held by the life company running it rather than by individuals.

Many savers also appear to have set up corporate accounts as companies are exempt from the directive.

Andrew Watt, head of tax investigations at Chiltern, a firm of accountants, said there was strong evidence that this was happening widely: “It’s the easiest thing in the world to do. You just leave the money where it is and instead of being held by Joe Bloggs it will be held by Joe Bloggs Ltd.”

Christine Ross, of SG Hambros, the private bank, said she was not surprised that the tax amount raised had been less than expected as most of her clients had opted to allow their European banks to exchange information about their accounts with UK authorities.

Under the directive’s rules, those opting to exchange information do not have a retention or withholding tax deducted from their accounts. Instead, information about interest accrued in the foreign-held account is handed over to the tax authorities where the account holder is resident.

Friday, August 11, 2006

Door Opens for trading volatility

By Paul J Davies - FT

Retail investors will soon be able to bet on the racy world of equity volatility – usually the preserve of hedge funds and proprietary trading desks at investment banks – after the launch of a new fund.

Dresdner Kleinwort, the German investment bank, and Kleinwort Benson, the private bank, are launching two open-ended investment companies in the UK that aim to profit from the difference between implied and realised volatility on the S&P 500 index.

The funds, thought to be the first of their kind, have been made possible by innovations in the derivatives market and by the Ucits III legislation, introduced last year by the European Commission and allowing mutual funds to invest in instruments previously banned.

It joins a growing number of special investment vehicles to be listed in London focused on areas such as hedge funds and structured finance. It aims to list in mid-September.

Trading volatility has become increasingly popular in recent years, while specialists such as Volaris, a unit of Credit Suisse in New York, now offer volatility management strategies to institutional investors.

Developments in the world of derivatives have opened the door to trading volatility through instruments such as variance swaps. These swaps are bespoke derivatives constructed to give exposure to volatility that will be used by the new OIECs.

Serge Desmedt, managing director in capital markets at Dresdner Kleinwort, said the idea for the new funds, called the Deva 80 and Deva 90 Alpha Funds, came from the trend that the level of volatility implied by the price at which equity options traded in the market generally overestimated actual or realised volatility.

Mr Desmedt said the trend was observable back to 1990. “It’s one thing to spot an arbitrage opportunity but quite another to execute it.” Mr Desmedt said new financial instruments allowed funds to do this now.

He added that the S&P 500 index had been chosen as the basis for the funds because it was the broadest and most liquid index. “We thought it provided the best stability of returns,” he said.

Andy Halford, head of structured products at Kleinwort Benson, said the new funds would offer an exposure to an asset class that had previously been unavailable to many investors.

He said trading equity volatility would offer an investment that had historically given attractive returns with low volatility and low correlation to other assets.

Thursday, August 10, 2006

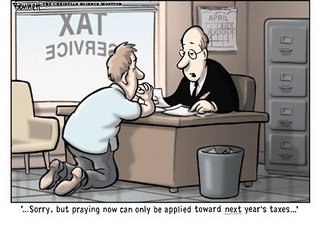

You like paying taxes?

"There is nothing sinister in so arranging one's affairs as to keep taxes as low as possible. Everybody does so, rich or poor; all do right. Nobody owes any public duty to pay more than the law demands; taxes are enforced extractions, not voluntary contributions!” - US Judge Learned Hand

The average UK citizen works from New Year's Day to May 24th solely to pay their taxes. Effectively, for a third of a year everyone in the UK is a civil servant. Income tax, national insurance, VAT, corporation tax, capital gains tax ... tax, tax, tax, the list is endless.

And that's not just in one year, that's every year. This happens all the way through your life. And after tax has been deducted, the little that remains is taxed again! If you spend it you're taxed. If you save it you're taxed.

How Little Of £100 You Get To Keep ...

Of £100 earned, 10% is paid in National Insurance contributions (nothing but a euphemism for an additional tax on income) and 22% is paid in Income Tax (40% for higher rate taxpayers). Of the remaining £68 of take-home pay let's say that over a week you spend it thus:

* £15 for a meal out

* £8 on cinema tickets

* £16 in petrol

* £3 put by for electricity

* £7 on some cigarettes

* £9 on a few drinks down the pub

* £4 paid out in insurance premiums

* £3 put aside for Council Tax

* £2 put by for Road Tax

Sound reasonable? Obviously 100% of the last two items are wholly tax. Five per cent of your electric bill goes to the taxman and 4% of any money you pay to protect yourself with insurance. Of the £23 you spend at the flicks and eating out, 17.5% goes to the government in VAT. While you're enjoying yourself, so is the Treasury; they take £4.03 from you for the evening.

35% of a well-deserved drink goes direct to our masters, and a recent AA campaign followed by the picketing of oil refineries serves to remind us that a staggering 85% of the money spent on petrol is snatched by the taxman. Eighty five per cent! But even that is not the worst. The state loves a smoker, of course, and from the money spent on cigarettes an astonishing 88.9% enters its coffers.

It brings tears to the eyes. Altogether, a full £32.31 of that week's expenses goes straight to the taxman.

Of the £100 earned, £64.31 will have been paid to the government in tax. At the end of the day, all you will have to show for it is £35.69 in goods and services. A higher-rate taxpayer will retain a miserly £21.69.

Oh, and we haven't even taken into consideration the host of taxes on business, employers national insurance contributions, airport taxes, capital gains tax ... and then there's stamp duty, where you hand over thousands just because you decide to move house! Somebody is taking us for a ride.

Don't think for a moment that European federalisation will stop with the Euro. The Germans are already making ugly noises about harmonising taxes throughout the community. In addition to the £11 a week every man, woman and child in this country contributes to the scandalously-corrupt EU, there'll be no escaping having to cough-up even more in tax – higher income taxes and higher purchase tax. When VAT rates are inevitably 'harmonised', books, newspapers, children's clothes and even our already over-priced food, presently with no VAT added, will increase by 20%... overnight! Does that thought sit comfortably with you?

No wonder the ex-Paymaster General, Geoffrey Robinson, secretes his considerable fortune offshore, tied up in unravelable trusts. A politician who knows how to make money knows how to keep it! Especially when he's privy to what's over the horizon. If tax avoidance is good enough for a Paymaster General, then I'm pretty sure it's good enough for the rest of us.

And look even further into the future. Whatever may be left at the end of your life doesn't escape the taxman either; a significant proportion of your estate... what you've managed to build up over the years will be taken in inheritance tax.

Marvellous, isn't it? You spend all your life trying to protect your family and build something for their future, and the government steps in and grabs a large chunk of it when you're dead and buried and hardly in a position to complain – just when the family you've left behind is at its most vulnerable. Civilised, aren't we?

The government trys to put a spin on those avoiding tax as, somehow, not good citizens, or they try to make it sound sinister and morally currupt. The simple fact is that it is your right to organise you tax affairs in the most efficient way possible. I started with a quiote from a US judge and I will end with a quote from a UK Law Lord, Lord Clyde.

"No man in the country is under the smallest obligation, moral or other, so to arrange his legal relations to his business or property as to enable the Inland Revenue to put the largest possible shovel in his stores. The Inland Revenue is not slow – and quite rightly – to take every advantage which is open to it under the Taxing Statutes for the purpose of depleting the taxpayer's pocket. And the taxpayer is in like manner entitled to be astute to prevent, so far as he honestly can, the depletion of his means by the Inland Revenue.”

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

BVI boom time for Asian REITs

Asian real estate investment trust (REIT) transactions are using offshore entities in the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands in increasing numbers, according to an analysis of the Hong Kong REIT market by Walkers, the offshore law firm.

“We have been involved in a significant number of the REIT transactions in Singapore and Hong Kong in the last 12 months. Direct investment into commercial real estate in China is also growing rapidly,” observed Hugh O’Loughlin, recently named managing partner for Walkers’ Hong Kong office.

According to a recent Standard & Poor’s report, the total market value of REITs across Asia, including Australia, recently exceeded the US$100 billion mark.

O’Loughlin continued: “One of the trends that we have seen is that both of these types of deals are using a mix of BVI and Cayman Islands entities in the same transaction. Since Walkers offers legal services for both jurisdictions, as well as Jersey counsel, we are in a unique position to be an integral part in some of the region’s most important projects.”

A recent significant development in Hong Kong's REIT market has been the announcement of the first REIT to be offered by a private firm. Shares of Charles Yeung’s trust could go on sale in late August or early September and are rumoured to raise up to US$350 million, according to Walkers. Another REIT is expected to raise up to US$750 million through a new bond issue.

“Another change that could really affect the market over the next several months is the expected move by Japan to allow REITs listed in Japan to acquire foreign properties,” noted Carol Hall, a partner in Walkers’ Hong Kong office.

“Hong Kong, Australia, and other countries already allow this as a way to diversify investments and reduce risk, so this is a sign that Japan wants to be competitive," she added.

In a bid to capitalise on the Asian REIT boom, Walkers has posted O’Loughlin and another partner, Philip Millward, to its Hong Kong office. Both were previously based in the Cayman Islands. Millward will focus on investment funds and private equity matters, particularly in Hong Kong, Australia, Korea, and Singapore.

Based in the Cayman Islands with offices in the British Virgin Islands, Dubai, Hong Kong, Jersey, and London, Walkers is one of the largest offshore law firms.

Walkers was named by HedgeWorld as the top law firm for hedge funds by total assets of funds and assets of non-US funds.

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Hedge Funds Are Back (Were They Ever Gone?)

By JENNY ANDERSON - New York Times

The hedge fund party seemed to be quieting down not so long ago. Returns were flagging. Blowout start-ups were fading from memory.

The hype and hyperbole are now back. Another star of finance is doing what all good stars do these days: start a really, really big hedge fund.

In September, Jon Wood, a former top trader with UBS, will start SRM Global Fund in Monaco, with commitments of more than $5 billion and capital of more than $3 billion to start with, according to people briefed on the fund. That puts him close to the record, set by Jack R. Meyer, the former investment manager of Harvard University’s assets, who raised more than $6 billion for Convexity Capital earlier this year.

It was not long ago that a $3 billion start-up had jaws dropping — and calculators clicking. Hedge fund managers tend to make a 2 percent management fee and take 20 to 25 percent of profits; 2 percent of $3 billion is $60 million. In November 2004, a former Goldman Sachs wunderkind, Eric Mindich, began Eton Park Capital Management with more than $3 billion. Last year, Dinaker Singh, who also hails from Goldman, started a $2.5 billion fund, which quickly soared to more than $5 billion.

Mega-start-ups, while less frequent, are arriving with a far bigger bang. Last year, 22 people started funds bigger than $1 billion, according to Chicago-based Hedge Fund Research. This year, only two hedge funds of $1 billion or more have been started: Mr. Meyer’s Convexity and Old Lane, run by Vikram Pandit and John Havens, former Morgan Stanley executives, who are said to have raised $2 billion to $4 billion. They did not return calls for comment.

While the stars seem to have no problems raking in billions, starting small is increasingly difficult, say people involved in fund-raising whose banks forbid them from speaking on the record.

“Raising $15 million to $50 million is much harder than it used to be,” said one fund-raiser.

Pedigree helps. Mr. Wood made roughly $500 million for UBS every year for at least half a dozen years, said one person who worked with him. Marketing materials indicate he never had a down month.

UBS, known for its conservatism, invested $500 million in his hedge fund. Management fees range from 1 to 1.5 percent, based on a three- to five-year lockup, and Mr. Wood and his team take 25 percent of the profits.

Some investors worry that traders like Mr. Wood, who come from a bank’s trading floor, will not be able to achieve the same high returns after leaving the mother ship. Banks are a treasure trove of people, ideas and capital flows, giving traders inside those organizations a clear edge.

But Mr. Wood has not worked on the physical main trading floors of UBS for years. He has operated from the Bahamas, Gstaad, Switzerland, and now Monaco. He told investors he did not need a large team because he has not operated with a large team for years.

Even losing a high-profile court case in London last year didn’t seem to dent Mr. Wood’s ability to attract billions. Mr. Wood and another minority shareholder in a retail chain brought a claim against Tom Hunter, a Scottish entrepreneur, over the acquisition of another retailer. The judge in the case called Mr. Wood an “evasive” witness who was a “very hard and calculating man.” UBS lost Sir Tom as a client of the private bank.

Mr. Wood will face many challenges, including investing $3 billion (and later $5 billion) successfully while running a business. His team includes four people. By comparison, Mr. Mindich began his fund with 50 people.

Obstacles aside, Mr. Wood is certain to be deluged by money coming from pension funds and endowments looking to get in hedge funds, and looking for a big name in particular. In the second quarter, investors gave hedge funds more than $42.1 billion, according to Hedge Fund Research, the highest level of inflows since the organization has been tracking flows, according to Joshua Rosenberg, president of Hedge Fund Research.

Returns, which soared in the first half of the year, have recently been rocky: down 1.54 percent in May and 0.15 percent in June. But for the year through July, the average fund is up 6.2 percent, compared with 2.7 percent for the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index.

The case for hedge funds may get harder. Recently, noncorrelated asset classes have become correlated, like gold and stocks. Many hedge funds sank with the equity markets they invested in. Interest rates are headed north, which should make cash look more attractive since hedge fund performance has averaged 9 percent over the last two years.

And yet, the money keeps coming in, inundating the established managers. To investors, these are hedge fund heroes, sent from Monaco, to return them to the days of over-the-moon returns. If they are not enough, there will be more: Ralph Rosenberg, a former Goldman trader, is expected to start a fund, R6, this fall with at least $1 billion and two former Goldman traders are planning to begin Montrica in Britain.

Expected size? More than $1 billion. Not so jaw-dropping anymore.

Monday, August 07, 2006

Goldman Sachs - Swiss Bankers?

With the reputation of Switzerland as the wealth management capital of the world, will Goldman be successful in its expansion into Europe or will the recent press about bank account secrecy being overturned by legislators in the US turn potential clients off. Heather Timmons discusses the latest expansion plans for Goldman.

By HEATHER TIMMONS - New York Times

Goldman, known for its prowess in trading and investment banking, has been quietly building up its international private banking business.

The firm plans to more than double the amount of private client investment managers that it has outside the United States, said Douglas C. Grip, managing director and head of private wealth management international at Goldman Sachs.

“We’re looking to grow dramatically over the next five years,” he said.

Goldman declined to give exact numbers, but that expansion would mean several hundred managers in Europe alone when it is done. Goldman is starting with a much smaller number of private client managers in the Middle East and Asia, but also has similar growth plans there.

Private banking was once the preserve of the Swiss banks — known as the gnomes of Zurich — and about a third of all private banking assets are still held in Swiss banks. But in recent years, private banking has become a fiercely contested field of battle, as banks seek to attract a growing number of very wealthy people, particularly from quickly expanding economic areas like Asia and the Middle East. The Swiss giants UBS and Credit Suisse are the leaders in managing the money of the wealthy, along with Citigroup, HSBC, Merrill Lynch and Deutsche Bank.

Goldman has far to go — it doesn’t make the list of the top 10 wealth managers, according to a Scorpio Partnership study released in June.

Goldman wants to wrestle market share from them in the future by offering access to its line of financial products, and also to pull in some clients from its corporate banking side, where it may already be giving some of these individuals advice about their corporation’s finances.

The bank is setting its sights high: it is focusing on investors with more than 10 million euros, or about $13 million, in assets to invest. Given that criteria, Goldman’s growth plans make sense: Scorpio Partners estimates that Goldman ranks among the top five managers for individuals with $10 million or more, though the bank has been so quiet about the business that Scorpio says many of the world’s wealthy do not know that Goldman wants to manage their money.

Goldman will reach smaller pocketbooks, too, through new joint ventures with dozens of local banks and family-run investment shops that will sell Goldman Sachs investment products under their own brand names. None of these joint ventures have been announced yet, Mr. Grip said, but there are several in negotiations.

“The industry is in constant change, and the best way to innovate is to combine great raw materials and superior intellect,” he said.

Goldman has expanded its private wealth assets more than 30 percent over the last four years, versus an industry average of growth of about 6.5 to 8 percent in that time, he said.

Despite Goldman’s high profile, people in the industry say the real test will be whether the bank can get its hands on new customers’ assets affordably.

“They certainly don’t have a bad brand name,” said Ray Soudah, the chairman of Millennium Associates, a consulting firm for private banks. The question is whether Goldman can mobilize its new network of private wealth managers to bring in new customers at a “reasonable cost,” he said. A majority of banks that have tried to build their own private banking networks have not succeeded, he said. “Hiring a few guys here and there will have a marginal effect,” Mr. Soudah noted.

To get where it would like to be in private banking, Mr. Grip said Goldman was not ruling out buying a Swiss bank. Goldman opened a Zurich office in 1974 and formed a Swiss private bank in 1992, but has been very quiet about its operations there. Switzerland has more than 300 private banks, and the industry has long been considered ripe for consolidation, but the asking prices are steep.

No matter how Goldman tries to increase its private banking business, it will never be a Swiss bank. And that is important to the wealthy of the Middle East, Russian businessmen and others who are drawn to the Swiss tradition of privacy. They may be worried about United States regulatory oversight, although Goldman says its Swiss bank is regulated by banking authorities in Switzerland.

Still, the potential for international private banking is huge. People are growing wealthier, faster, in areas outside the United States than within it, according to a Merrill Lynch/Cap Gemini study. There are 8.7 million millionaires worldwide, and about 85,400 individuals with net financial assets worth more than $30 million, the study said. The percentage of millionaires grew by double digits in South Africa, India, South Korea and Russia in 2005, the survey said. In North America it grew by 6.9 percent.

Goldman already has some private banking operations, though in its financial results it lumps these assets in with institutional money it manages, so getting a sense of their current size is difficult. In the United States, Goldman operates its private wealth management business through 13 regional offices, which have been undergoing some upheaval of their own, including staffing changes, as the bank revamps the business.

To woo private banking clients, one thing Goldman may need to overcome is its own success in aggressively investing money for the firm itself. Mr. Grip acknowledged the firm’s reputation, but said that Goldman was just as capable of building a portfolio for conservative investors, one that would focus on “sleep-well money.”

Friday, August 04, 2006

Buy Out Firms to add Hedge Funds

By Edward Evans and Ambereen Choudhury

LONDON Carlyle Group and Blackstone Group, two U.S. buyout firms that announced more than $30 billion worth of takeovers in the past 12 months, are starting hedge funds as the industry grows at the fastest rate in three years.

Carlyle is close to hiring Ralph Reynolds, who is based in New York as Deutsche Bank's global head of proprietary trading, to run a new hedge fund unit, The Wall Street Journal reported Tuesday, citing people familiar with the decision. Blackstone recruited Manish Mittal in April from Perry Capital of New York to run a planned $1 billion hedge fund.

Leveraged buyout firms are searching for new ways to increase profit as financing costs climb and competition between firms for the same assets intensifies. Investors pumped $42.1 billion into hedge funds during the second quarter, the biggest quarterly inflow since at least 2003, according to data compiled by Hedge Fund Research in Chicago.

"Why limit yourself to private equity?" said John Godden, chief executive officer of IGS Group, a hedge fund advisory firm based in London. "From a commercial perspective, they are going to be able to raise more money and get more fees."

During an interview by telephone from his office in New York, Reynolds said that he was still an employee of Deutsche Bank. He declined further comment.

David Rubenstein, co-founder of Carlyle, which oversees about $42 billion of private-equity funds, said earlier this year that the company was considering opening hedge funds. By creating hedge funds, the firm based in Washington can expand its range of investments in stocks, bonds and commodities.

"It would be quite some time before our hedge fund business could become quite that big," Rubenstein said in January. "It's clear there's a fair amount of capital looking for good returns and hedge funds offer a different kind of risk to private-equity funds."

Carlyle in 2003 sold its hedge fund unit, which had about $600 million of assets, to the division's managers after two years in the business.

Texas Pacific Group, a U.S. buyout firm, has a partnership with TPG-Axon Capital Management, a $5.8 billion hedge fund started in 2004 by former Goldman Sachs Group partner Dinakar Singh.

Hedge funds returned 6.2 percent in the first half of the year, compared with 2.7 percent for the Standard & Poor's 500-stock index, a benchmark for U.S. stocks, according to Hedge Fund Research. Industry assets have more than doubled to about $1.3 trillion since 2000.

Hedge funds are designed for investors with at least $1 million, and endeavor to make money whether financial markets rise or fall. They can use leverage to help increase gains and they can sell short, or borrow securities and immediately sell them with the hope of buying them back at a lower price.

They typically charge an annual fee equal to about 2 percent of assets and the fund managers keep 20 percent of any investment gains. Leveraged buyout funds tend to charge investors an annual management fee of 1.5 percent. They also keep 20 percent of the profit, usually once the fund has returned all the cash it invested, a process that can take years.

Buyout firms use a mix of their funds and debt to pay for takeovers. They typically seek to expand companies or improve performance before selling them within five years to other funds or investors through stock offerings.

Carlyle forming team for the Middle East

NEW YORK: Carlyle Group, manager of the biggest U.S. buyout fund, wants to start a Middle East team to invest in the oil-rich region, which is flush with cash after prices almost quadrupled in the past 4½ years.

The firm has not decided where it would base the team or how many people it might hire, a spokesman, Chris Ullman, said. He declined to comment on whether the company, which is based in Washington, would raise a Middle East buyout fund.

"We're looking to establish a Middle East investment team, and for someone to head that office," Ullman said during an interview Monday.

The Gulf economies have boomed as oil prices have risen to more than $74 a barrel from under $20 at the end of 2001. Abu Dhabi, the largest sheikdom in the United Arab Emirates and the location of most of the federation's crude reserves, had oil revenue of more than $31 billion last year, according to Standard Chartered. $@

Mellon starts unit for wealthy Britons

EDINBURGH: Mellon Financial, which administers about $4.9 trillion in client assets, said Tuesday that it was starting a new unit for wealthy British customers, its first such division outside the United States.

Jim McEleney will run the unit, which will seek to administer assets of families that have at least $50 million to invest. Many wealthy families have employees who administer their assets or private banks that invest on their behalf.

"There are about 1,000 families in that market in the U.K.," McEleney said during a telephone interview Tuesday from his office in London. "This also gives us a springboard into Europe."

Fund administration and custody services cover all aspects of fund management other than investment decisions. Fees typically are much lower than for managing money and the contracts as a result tend to cover larger amounts of assets. Mellon's U.S. business administering assets for wealthy clients has about 130 clients with $32 billion of assets. $@ - David Clarke

$4.6 billion withdrawn from Fidelity in June

BOSTON: Fidelity Investments, the largest mutual fund company, had $4.6 billion in investor withdrawals in June, the most among peers, data from Financial Research show.

Investors removed $1.1 billion from the company's stock and bond funds in May. Industry redemptions were $2.7 billion, compared with net inflows of $5.3 billion in May, according to Financial Research, also based in Boston.

Investors pulled money out of stock and bond funds after the global markets tumbled in May on concern that rising interest rates would stem economic growth. The Standard & Poor's 500- stock index has dropped 3.6 percent after reaching a peak in early May.

State Street Global Advisors led sales in June, pulling $5.9 billion into its exchange-traded funds. American Funds, a unit of Capital Group of Los Angeles, was in second place, gathering a net $3.1 billion.

Thursday, August 03, 2006

Funds in the Dog House

by Yahoo Business

Investors have more than £8 billion in poor performing "dog" funds - a massive increase of more than 160% over the past six months. And some of the worst offenders are big names, such as Prudential and Scottish Widows.

A fund is kicked into the dog kennel if it has failed to beat its benchmark in each of the last three years. It must also have underperformed its benchmark by at least 10% over the 36 months, according to the Spot the Dog Guide, published by Bestinvest, an independent financial adviser. It names and shames 52 funds - up from 38 in the previous six-monthly study.

The biggest "dog" funds

The worst offender by value is the 'flagship' £2.2 billion Prudential UK Growth fund, which is managed by M&G. The fund is actually worse than a dog because it has also failed to beat the FTSE All Share in eight of the last 10 years. It's a pretty poor show - but a profitable one for the fund manager. Based on the current fund size, investors collectively pay Prudential over £33 million a year through the 1.5% annual management charge. How can Prudential justify charging so much for so little?

Mark Hinton, a fund analyst at Bestinvest, says: "Too many fund managers turn in mediocre performance, failing to add enough value to compensate for charges." The Pru argues that it has taken steps to improve the performance of the fund with a change of manager this year, but why did it take so long?

Henderson has made no less than 12 fund manager changes over the last two years in an effort to boost performance. However, it still has three large dogs - Growth & Income, UK Equity and European - with a total of £1.1 billion. And most of its funds have failed to beat their benchmarks over the last year, so there's little evidence yet of improvement.

In third place is St James's Place with £667 million in its one dog fund, the UK & General Progressive. The fund has a fairly decent long-term record, but it was wrong footed by the recent strong performance of the stock market.

Who's to blame?

You can't put the woeful performance of Canada Life's two dog funds (£663 million) down to poor timing. The managers of Canlife Growth have done so badly over their career that Bestinvest estimates there's only a 1 in a 1,000 chance it was due to bad luck. In other words, don't expect a turnaround any time soon. They are probably not very good fund mangers. The prospects for the other dog fund, Canlife General, don't look much better.

Scottish Widows has £656 million in dog funds. January's worst offender has fallen several places but it's mainly thanks to the influx of big dogs from other groups rather than any fundamental improvement in Scottish Widows' performance. Again, there have been some changes - more than 18 funds have switched manager over the past two years. But it's not really helped: more than half the group's funds have failed to beat their benchmark over the last year.

The £443 million First State Global Emerging Markets fund makes its third consecutive appearance in the list of shame - and it's disappointing. The manager, Angus Tulloch, has a good reputation built on a robust long-term record, but his cautious approach has not served him well recently. The fund has picked up over the last couple of months, but Tulloch still has a long way to go if he's to climb back up the performance charts.

Falling stars

'Star' managers are not immune to bouts of poor performance and the recent stock-market volatility seems to have caught a few out, particularly some of the more aggressive managers. Carl Stick, who runs Rathbone Special Situations, and James Ridgewell of New Star UK Special Situations were among the biggest fallers.

Does the big increase in the number of dogs mean fund managers are getting worse? Justin Modray of Bestinvest thinks not. He says: "The number of dogs historically tends to fall when volatility is low and rise when it is higher. The recent increase in volatility means we're likely just seeing the number of dogs starting to return to their natural level."

Time to switch

If you have money in a dog fund, you should not automatically switch. Past performance is not always a guide to the future. Last year, for example, F&C analysed the performance of more than 5,000 funds since 1995 and found that two thirds of the worst performers over three years were no longer in the bottom quartile two years later. Almost one in four had climbed into the top quartile.

But you need to have a good reason to hold onto the fund. For example, a poor manager might have recently been replaced with a better one, or a skilful manager may have simply suffered a poor short-term run. It sounds like an excuse, but different stock market cycles can really play against different investment strategies.

If your fund is a persistent poor performer, you should have a rethink. You should also give your adviser a call. Advisers normally take renewal commission each year, so you need to know what they are doing for the money.